Today, most people get their news from social media feeds, where extreme political polarization is common. This makes media literacy crucial for audiences to distinguish fake news from real news.

Watch this TED Talk where Lisa Remillard, a former television journalist and current journalist influencer, discusses how to spot misinformation in the news.

…the term “fake news” has become highly political and is often used as a buzzword not only used to describe fabricated information but to undermine the credibility of news organizations or argue against commentary that disagrees with our own opinion…

Molina et al., 2025. p. 184

What is Fake News?

Fake news is defined briefly by Molina et al. (2021) as “fabricated information that is patently false” (p. 180).

Pexels, 2020

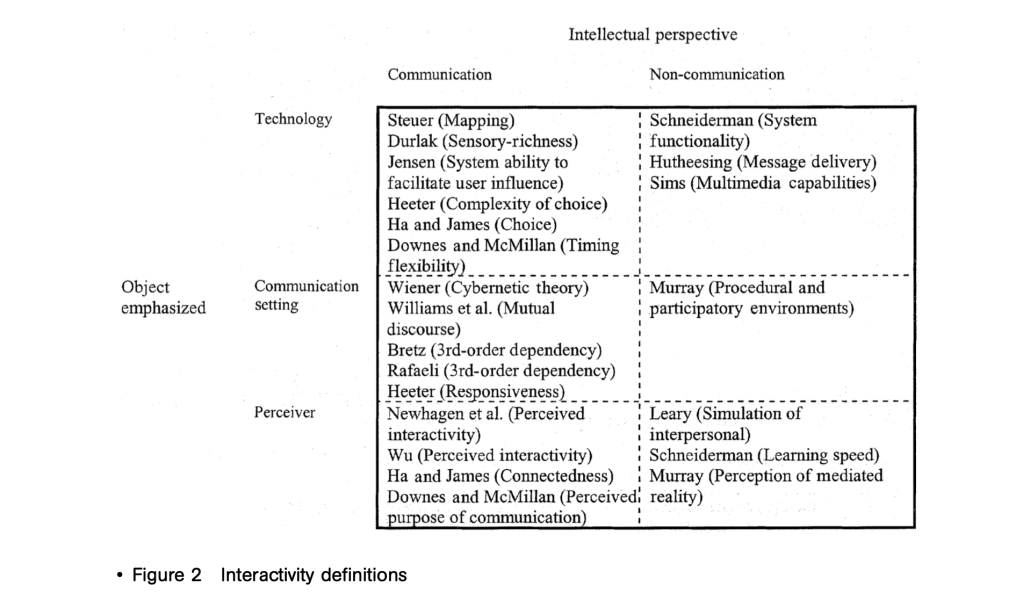

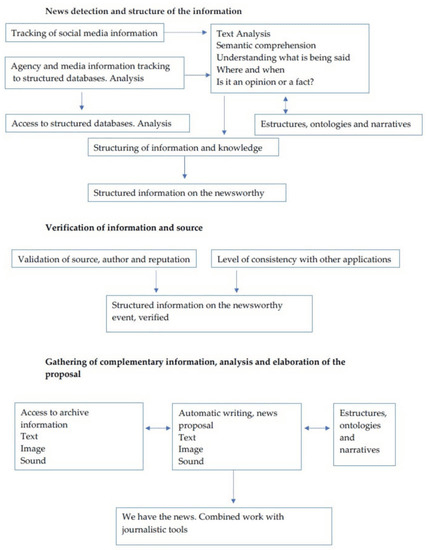

Given the rising popularity and divisive nature of the concept, Molina et al. (2021) aimed to explain fake news using eight categories of online content that a machine-learning algorithm can use to determine whether a piece of information is fake news or legitimate news.

This analysis included the following categories: “real news, false news, polarizing content, satire, misreporting, commentary, persausive information, and citizen journalism” (Molina et al., 2021, p. 186).

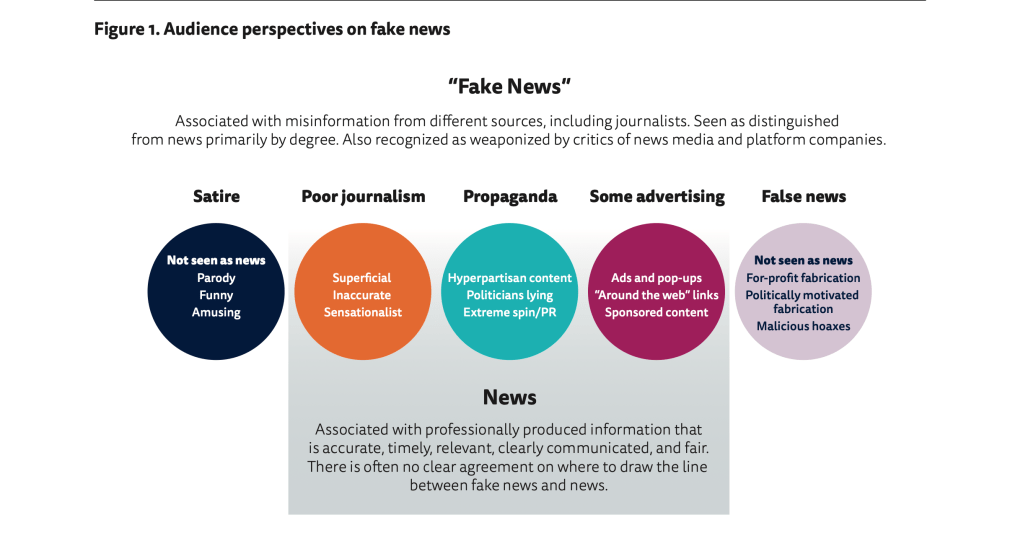

Nielsen & Graves (2017) studied audience perspectives on fake news and found that “People see the difference between fake news and news as one of degree rather than a clear distinction” (p. 1).

(Nielsen & Graves, 2017, p. 3)

What is Misreporting?

Misreporting is a type of misinformation. Misinformation is not to be confused with disinformation. “While ‘misinformation’ can be simply defined as false, mistaken, or misleading information, ‘disinformation’ entails the distribution, assertion, or dissemination of false, mistaken, or misleading information in an intentional, deliberate, or purposeful effort to mislead, deceive, or confuse” (Fetzer, 2004, p. 231).

Misreported information is disseminated without direct information from sources and verifiable qoutes (Molina et al., 2021).

Key Similarities and Differences

Understanding the difference between fake news and misreporting is crucial, as it emphasizes the need for media literacy. They differ in terms of intent, authenticity, source, and how false information is handled after being uncovered.

Fake news is spread with the purpose of deceiving or harming the public. It involves entirely or mostly fabricated content originating from sources that do not follow editorial standards. Since the aim is to spread falsehoods, no corrections are typically made.

Misreporting can happen even when journalists have good intentions. It involves information based on real events or facts, but is presented with errors or lacks proper context. The source of misreported information is usually a reputable news outlet. Once false information is identified, responsible outlets aim to correct or update the content they have shared.

Keywords: fake news, misreporting, media literacy, political polarization, social media, concept explication

References

Fetzer, J. H. (2004). Disinformation: The use of false information. Minds and Machines, 14, 231-240. doi:10.1023/B:MIND.0000021683.28604.5b

Molina, M.D., Sundar, S.S., Le, T., & Lee, D. (2021). “Fake News” is not simply false

information: A concept explication and taxonomy of online content. American

Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 180-212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219878224

Nielsen, R. K., & Graves, L. (2017). “News you don’t believe”: Audience perspectives on fake news. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:6eff4d14-bc72-404d-b78a-4c2573459ab8/files/snp193c257

Remillard, L. (2024, August 27). Media and Democracy: Finding Facts in the Mess of Misinformation | Lisa Remillard | TEDxBillings [Video]. Tedx Talks. Youtube.